If my title irritates you, it should. We got Zen breakfast cereal, and Zen memes of someone in a leotard on a mountaintop. No mention of how that fresh feeling comes from rigorous if not painful continuous attention to reality.

This post is about actual Zen and how it relates to concise writing, based on its origin in the transmission of a view, Buddhism, from an alphabetic-language culture, Sanskrit India, to a pictographic-language culture, ancient China.

From here I shall use the Chinese term Ch’an instead of its laterJapanese derivative Zen, because I’m discussing the origins of Ch’an in China in the sixth century AD.

The “Nature” of Pictographic Language

David Abram is a 21st century philosopher of nature. His work connects a biocentric worldview with phenomenology, which claims our relationship with the world through perception to be more important than an objective reality we decipher abstractly from data. He asserts animism as a valid worldview.

In his book The Spell of the Sensuous he speculates on society’s transition from pictographic writing to alphabetic writing (with my ellipses for concision):

Some historians and philosophers have concluded that the Jewish and Christian traditions, with their otherworldly God, are primarily responsible for [Western] civilization’s negligent attitude toward the environing earth … Other thinkers, however, have turned toward the Greek origins of our philosophical tradition … for the roots of our nature-disdain … In every other respect these two traditions … were vastly different. In every other respect, that is, but one … they both made use of the strange and potent technology which we have come to call “alphabet.”

With the advent of the aleph-beth, a new distance opens between human culture and the rest of nature. To be sure, pictographic and ideographic writing already involved a displacement of our sensory participation from the depths of the animate environment to the flat surface of our walls, of clay tablets, of the sheets of papyrus. However … the written images themselves often related us back to the other animals and the environing earth … With the phonetic aleph-beth, however, the written character no longer refers us to any sensible phenomenon out in the world … but solely to a gesture to be made by the human mouth … Human utterances are now elicited, directly, by human made signs; the larger, more-than-human life-world is no longer part of the semiotic, no longer a necessary part of the system.

When discussing the ancient roots of Western society, this is intriguing. But applying this logic to cultures that still use pictographs, such as China and Japan, we risk a romantic racial stereotype. However, classical Chinese has thousands more characters than modern Chinese. While less people could master it, it was closer to Abram’s ideal of a pictographic language closer to the natural world.

And even with this in mind, I can’t help notice in these modern tech titans, Tao and Shinto are still-thriving nature-based religions with no Western equivalent. As a neuro-divergent slob, I recently read Marie Kondo’s The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up: The Japanese Art of Decluttering and Organizing. Her Shinto outlook on objects is as animist as anything David Abram could dream of.

Sanskrit and Classical Chinese

Buddhism spread through more ways than history knows, from the Caucasus to Siberia to Indonesia. One of the best known ways is the journey of the legendary Bodhidharma in 527 AD from India (or Persia?) to China where he founded Ch’an.

In the West we often lump India and China together as the “East.” But Indian languages such as Sankrit and Pali are Indo-European like Latin and English, with precise and complicated verb forms, and lots of helping words. In written Chinese, pictographs represent the main concepts, and the relationships between them are determined by context if not intuition.

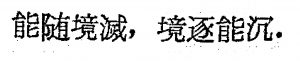

See how this Chinese phrase from the Ch’an classic Hsin Hsin Ming is translated into English in many ways:

No offense offered, and no ten thousand things; No disturbance going, and no mind set up to work. D.T. Suzuki

If things are unblamed, they cease to exist; If nothing happens, there is no mind. R.H. Blythe

And when no thing can give offense, then all obstructions cease to be. Phillip Kapleau

When a thing (dharma) can no longer offend it ceases to exist in the usual way. When discriminating thoughts do not arise (old mind) the usual mind ceases to exist (dualistic mind) Sojun Mel Weitsman

Often the translations seem to vary in actual meaning. More relevant however: they vary in how literal is the transcription and in the use of modern terms to avoid possibly obsolete idioms and metaphors. And they vary in length: some try to capture the flavor of intuiting connections, and some flesh out the ideas for the benefit of alphabetic readers. The approach can depend on whether the translator is a philosopher, a teacher, a scholar or a poet. The last version is from my teacher; as many words as needed are used for the benefit of students unused to lateral thinking.

Taoism and the Ghost of an Alphabet

A common explanation of how Ch’an differed from Buddhist in South Asia is that it is a fusion of Buddhism and Taoism. This must be true at least in part; Buddhism is famous for its capacity to adapt to foreign cultures. However, consider how by translation into Chinese language, Buddhism must also translate into Chinese culture.

An alphabetic system translating into pictographs will be very different from an originally pictographic system like Taoism. Consider back-to-the-land types moving in amongst families who’ve farmed for generations. If they want to succeed they had better respect their “redneck” neighbors, but in time they may have something to offer their new community.

I suspect that the loss of Ch’an’s linguistic origins leads to over-mystification. For example, we often claim Ch’an koans, stories or quotations transcend rational thinking. Though some koans are clearly intended as riddles, note how above, the brisker, more literal translations resemble Koans. Often, an idea, once translated from Sanskrit to Chinese, is translated literally into an alphabetic language such as English, and we say, “One cannot grasp the deep meaning with rational thinking.” As if “intuition” or some other mortal power can grasp the entire deepest meaning of anything (Life’s rough).

Zen and the Art of …

We writers aim to capture in our prose many of the characteristics of stereotypical Zen. We want our writing to be full of life, no dead pixels. Every word counts. Direct. The reader should be captured by the image and the meaning, not the sentence structure.

So naturally there are books on Zen and writing. Perhaps the most famous is Natalie Goldberg’s Writing Down the Bones, which recommends writing first drafts in the spirit of Zen: not letting the monkey mind get in the way of spontaneous expression of one’s true nature, saving any editing or revising for later. However, that later editing and revision is what I’m talking about in this post, and I haven’t heard that discussed before.

I’m in favor of applying Westernized Zen to writing; that’s the starting point of my exploration here. But when we do this, we’re taking an alphabet version of a pictographic version of an alphabetical idea, and by making it vivid and likely,making it pictographic again.

I suggest that, perhaps in conjunction with the above method, we claim the benefits of pictographic cognition directly. We want the best of both the alphabetic and pictographic worlds, yes?

… Concise Writing

I’m writing to you in English; you and I can’t avoid the alphabet. But we can take the benefits of pictographic reasoning where we can get them. The emergence of Ch’an illustrates is the benefit of directness:

“When you do something, you should do it with your whole body and mind; you should be concentrated on what you do. You should do it completely, like a good bonfire. You should not be a smoky fire. You should burn yourself completely.”

Sunryu Suzuki

One aspect of this in editing is “character and action.” Often the main ideas, a doer and an actual action, the ones that would get pictographs, are not the main subject and verb,. In this sentence:

The proper drafting of treaty requires collaboration between dwarves and elves in deciding objectives and time frames.

The subjects is “drafting” and the verb is “requires.” But the actors are the dwarves and elves, and the actions are collaborating and deciding:

To draft a treaty, elves and dwarves must collaborate to decide objectives and time frames.

Another crisp thing about a pictographic language is not-a-lot of helping words. And definitely no useless words.Here are five principles of concision, from Style: The Basics of Clarity and Grace by Josephs Williams and Bizup. Italics their words and plain text my commentary.

1. Delete words that mean little or nothing. Kind of, actually, certain, basically. Imagine a classical Chinese calligrapher diligently drawing these nothings!

2. Delete words that repeat the meaning of other words. True and accurate, first and foremost. The Style Josephs note a fascinating history fact: this silly practice started when Middle English speakers paired a Latin-based word with an Anglo-Saxon one so speakers or all classes would understand. The great difference between Sanskrit and Chinese prevented this in Ch’an.

3. Delete words implied by other words. Terrible tragedy, future events, period of time, large in size,game of chess.

4. Replace a phrase with a word. An extreme example from the Style Josephs:

“As you carefully read what you have written to improve wording and catch errors of spelling and punctuation, the thing to do before anything else is to see whether you can use sequences of subjects and verbs instead of the same ideas expressed as nouns.”

This transforms into, “As you edit, first replace nominalizations with clauses.” As, in accordance with David Abram, we want our readers to think of what were saying rather than our words, one word evoking a picture is worth a thousand junk words.

5. Change negatives to affirmatives. Not often becomes rarely, not include becomes skip. A Zen paradox: New age theorists claim that in the brain levels accessed by meditation, there are no negatives; a dog can only hear “walk,” never “no walk.” And there’s an obvious directness and liveliness on saying what someone is rather than isn’t. However, “The Tao that can be told is not the eternal Tao,” wrote Lao Tzu. When talking about something beyond words, we might settle for what it isn’t. Thus the core text of Ch’an, “The Heart Sutra,” is so full of no’s I call it the “No Sutra:”

https://brooklynzen.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/Heart-of-Great-Perfect-Wisdom-Sutra.pdf

So be mindful with all the posi-ness!

6. Delete useless adjectives and adverbs. Self-explanatory. If you’re reading this, you likely are involved in fiction. Common fiction advice is to avoid adverbs.

In fiction, we have the ability to alter reality so our writing doesn’t distract from it.. Example, “Beowulf arrived just before two.” Or for that matter, “Beowulf arrived exactly at two.” If this really happened, you may say “just before two” or “around two” to be accurate. In fiction, if you write, “Beowulf arrived at two,” such imprecision likely has no effect on the story.

While this post is about how not to entangle the reader is “prose,” the next part will be about staying in the main storytime, the present even when the story is in simple past tense. If that’s the present, and the present is when we can be fully alive, how do we handle the past and future?